Photo Credit @http://www.mediamath.com

Dear Doctor,

I came to your office today to meet you for the first time. I brought along my 12 year old daughter who has a variety of medical conditions. We’ve been accumulating diagnoses since she was born and at a great rate in the last few years.

As her mother, I am a typically healthy person, privileged with a body that’s never been diagnosed with anything chronic or painful. I’ve been “able” to do anything I’ve desired for the past 43 years.

When I came to your office today, we began with me filling out paperwork and paying you money. I am lucky to have insurance. I spent part of my work day and $50 so we could learn from you. I believe the insurance company will pay you additional fees for our time with you and the opportunity to learn both about the condition you are diagnosing my daughter with and the treatment options you are prescribing.

We moved in with your nurse who would weigh and measure my daughter.

We passed you on the way to the scale and the wall mounted height rod. You looked like the doctor. I thought it made sense to greet the person we were here to see with a good morning. You ignored us. The nurse measured my daughter.

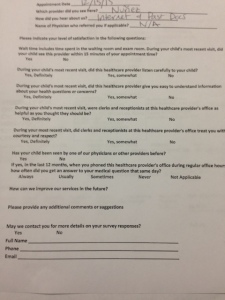

We were escorted to an examination room. I received a clipboard and began responding to the review of systems form.

You entered the room. I’m not sure you shook our hands or greeted my daughter. You were holding a report in your hand. You read it over to yourself and spoke about the new condition you think she has. You asked me why we had come to you. I told you that we had not observed any issues, but had been referred by a surgeon who had told us a consult and test with you were part of his new patient protocol.

I told you another doctor had told us she did not think we had the condition you were diagnosing, so this doctor’s referral for the test was a counter to your test and diagnosis.

You shifted in your seat. This seemed to discomfort you.

You rated my daughter’s condition with a numeric scale.

I asked you what the highest rating on the scale was, so I had something to compare the number you were giving me to.

You said the scale had no upper bound.

I asked you how the rating gets configured. What measures are taken and how are they used to determine my daughter’s rating on this scale?

You stared at me. Time passed. You told me some terms and some numbers.

I asked you what the terms meant.

You stared at me. Time passed. You defined the terms.

I asked you what sorts of issues might arise during the study that would confound or complicate the data gathered. If you were the parent using the study to make meaning of a diagnosis, what questions might you have about the conditions of the study?

You barked that data had been captured about my daughter for well more than the minimum amount of time required by the American Academy of Pediatric Doctors in your subspecialty.

This didn’t answer my question directly, but it was the last question I asked.

I felt like I had to explain myself.

I felt like you did not want me to ask questions.

I felt like you wanted me to accept your diagnosis and follow up with your recommended treatment.

I had more questions and I saved them for the internet.

I had more questions and I did not ask them.

Dear, doctor, what is your health status?

Do you have any children? If so, what is their health status?

How many doctors have you visited with young children carrying multiple diagnoses?

Do you know much about my daughter’s rare genetic mutation and resulting condition? What do you know of my experiences working with world renowned doctors?

I know some about my daughter’s condition, but I don’t know everything. In fact many doctors who have tested and diagnosed and treated her do not know everything. Most of them know very little about her condition and most of them know very little about her history. Even doctors who study her condition do not know everything.

But I have lived with her for 12 years. I am well versed in her bodily history. I am also well versed in what it’s like to get inaccurate diagnoses. I am well versed in what it’s like when doctors treat her as though she has only the condition they are familiar with. I have seen her over and under dosed. I have seen her receive conflicting diagnoses. I have seen her accidentally get better equipment that better treats her symptoms because a random operator or therapist mentioned an option the doctor knew nothing of. I have seen her get the wrong medication. I have been sent to different specialists because the specialist was so sure of their diagnosis only to find out a year later they were wrong. I am well versed in what it’s like to live in a hospital for three weeks after a routine surgery sends my daughter into respiratory arrest because she is treated like a child without a genetic disorder. These are only some of my experiences.

What is hers?

I have seen my daughter’s face grow sullen as she is talked about. I have seen her frustrated by a body she was born with that seems to both transfix and distance people as they bounce between inquisitive stares, averted eyes and bright stiffly smiling teeth. Strangers work hard to speed past us while getting enough eye contact with me that I know they “admire” me and sharing enough smiley eye contact with her that she knows they feel sorry for her. But few want to know her or be her friend. Curiosity and exchange are signs of love. Smiles, questions about my daughter’s shoes or school and speed create a comfortable distance for doctors and street strangers, but a dangerous distance for me and my daughter.

I use my questions and story sharing to close this distance – often to the chagrin and frustration of doctors, educators, peers, friends and sometimes family. This is my job as a mother, a parent, an advocate and now a mentor to my daughter as she learns to self advocate in all the appointments and situations she will find herself in as a youth and adult. There will be so many times and places where people will know and feel much less than she does about herself, but will use their power and position to shame, doubt, or negate her inquiries and interests.

So where do we go from here?

This is a city where we might run into one another and doctors know doctors and one might run out of second and third opinions, so it’s important that we build a better medical community right here. We cannot simply move on. I cannot run from this. There are not infinite local options, so these are my suggestions:

First, I want you to see my daughter for the person she is. Greet her. Introduce yourself. Ask something about her.

Second, I want you to see us as people who see lots of doctors all the time. Each year, my daughter has well visits with:

A neurologist

A neuropsychologist

An endocrinologist

A craniofacial surgeon

An orthodontist

A nephrologist

An otolaryngologist

An ophthalmologist

A urologist

A prosthodontist

A dentist

A pediatrician

And now you

This does not include illness, changes, tests or additional consults.

Now, I need you to think about how that feels over time. How does it feel to get another diagnosis when you already have 8? What do you think my daughter is thinking as you talk about her and what I should do in front of her? She is staring at the floor. Is she scared to be here? She is here. Acknowledge her. Speak to her. Don’t let her get comfortable being spoken about, touched and examined without being humanized. That is a dangerous position for any human patient and for you. It denies you the opportunity to practice informed, patient and family centered medicine. It denies you the opportunity to learn about her context and adjust to her needs.

Lastly, I want you to know how much power you have to support young people moving into managing and self advocating for their own medical care. Teach my daughter how to care for herself, how to be treated fairly and thoroughly, how to ask her doctor as many questions as she can, how to talk to a doctor about her experience and her hopes, how to think critically like you do. I know you are a critical thinker and now I need you to make your exam room a place where other critical thinkers are welcome and mentored into self care and advocacy for a strong, healthy future as informed citizens.

People first,

Liz, mother to one of your patients

And there is Sadie, looking around, distracting herself, wondering, studying, worrying about me…I’m pissed that she worries about me. I’m pissed that the doctor is putting me in a position where I am supposed to play the parent with expectations she is going to work on in front of my child. If Sadie invites me to a therapy session with her when she is 27 and we have to work through this doctor’s office visit, I won’t be surprised. The position this produces for her makes me sick to my stomach…makes me have to write this.

And there is Sadie, looking around, distracting herself, wondering, studying, worrying about me…I’m pissed that she worries about me. I’m pissed that the doctor is putting me in a position where I am supposed to play the parent with expectations she is going to work on in front of my child. If Sadie invites me to a therapy session with her when she is 27 and we have to work through this doctor’s office visit, I won’t be surprised. The position this produces for her makes me sick to my stomach…makes me have to write this.